For more than 30 years, John Pollock has spotted the magic in everyday students, turning them into national-stage researchers.

Words by Liz Leyden

Photos: Peter Murphy

When Tom Hipper ’07 hopped on a plane at the tail end of his junior year to fly to Kentucky, he knew the trip would be special. Not only was he about to attend one of the most prestigious health communication conferences in the country, but he and another TCNJ student had been tapped to discuss their research in front of the field’s heavy hitters.

But nothing prepared Hipper for the moment when the crowd realized, with a gasp, that they were listening to the first undergraduates ever invited to present their work at this event. “We just felt like rock stars,” he says. “People couldn’t believe how young we were. Like, ‘Where the hell did these two come from?’”

The quick answer to that question was a small college hundreds of miles away from the state where they stood.

But the even better answer revolved less around a place than a person — a TCNJ professor on a mission to foster serious scholarship, to convince every one of his students that they could do research and write papers and stand toe to toe with the very experts whose work they studied in class.

The truest answer — and the heart of the story for Hipper and hundreds of students before and since — was John C. Pollock.

And on that day, when the crowd at the Kentucky Conference on Health Communication gasped and showered his students with well-earned accolades, Pollock was there, too, proudly cheering them on. “It just doesn’t get any better than that,” Pollock says.

Since arriving at TCNJ in 1992, Pollock has shaped the lives of generations of students with a distinct and determined teaching style designed to launch them into the world — not once they graduate, but as soon as they step into his classroom.

Over the past three decades, more than 600 students in Pollock’s communication studies and public health courses have co-authored peer-reviewed papers on critical social issues, including immigration reform, reproductive rights, and child labor. They’ve packed their bags and traveled to more than a dozen cities across the country to present their work at conferences with academics and communication professionals already decades into their careers. Along the way, they’ve collected top awards from the National Communication Association, studied in South Africa, and done research for the United Nations.

The achievements belong to the students, but year after year, Pollock has served as the spark that lights the flame. With an endlessly open door, he helps them wrestle with ideas, land internships, apply to graduate school, and map their futures. He makes them believe in all that is possible. “So much of his career has been about helping his current batch of students start down this path and do cool things,” says Hipper, an assistant clinical teaching professor and associate director of the Center for Public Health Readiness and Communication at Drexel University. “It’s pretty amazing to see someone just almost entirely devoted to their students’ success.”

This fall, Pollock, now 82, began what will be his final year at TCNJ. For many grateful alumni, the moment is bittersweet; he’s the kind of professor whose imprint extends long after graduation. “I’m explicit about saying, ‘We’re friends for life, so reach out anytime,’” Pollock says.

And they do. On any given day, years after they’ve collected their diplomas, Pollock’s former students call him for job advice and pep talks and to announce publications and promotions. They invite him to their graduation parties and weddings and to the birthday parties of their children.

This coming spring, they will call with heartfelt congratulations, amazed he’s actually retiring; they thought he might stay at TCNJ forever. The decision to leave surprised Pollock, too. “I always thought I would die here, because I love teaching,” he says.

Pollock ’s zeal for education emerged during his boyhood in Dallas, where his godmother regularly took him to nearby Southern Methodist University to watch the commencement procession. The first time he glimpsed the faculty in their academic regalia — which he called “wizard costumes” — he was entranced. “I wanted to be one of those magical guys,” he says.

At Swarthmore College, Pollock studied political science and international relations and discovered a passion for research. But it was his professors’ interest in student ideas that changed his world. “It was very much, ‘Your opinions are as valid as mine,’” he says. “We’re all smart people here. The professors had just been at it a bit longer.”

That spirit would anchor Pollock’s teaching philosophy, as would his experiences conducting fieldwork in India while earning his master’s degree in international public administration from Syracuse University and pursuing his PhD at Stanford. He carried the best parts of

his education into his own classroom. Pollock taught political science and communication classes at Rutgers University and then at the City University of New York. But he also had a young family to support. So after a decade of teaching, Pollock made an unexpected detour to a public relations career. Despite success conducting public opinion research and operating his own communication firm for seven years, he missed teaching.

In 1992, in his attempt to find a job back in academia, Pollock rang the communication studies department at TCNJ. To his relief, they hired him. “I will always be indebted to TCNJ for hiring me,” he says. “I had been given a new life.”

He arrived energized and ready to make up for lost time, setting goals for his classes that soared past simply mastering the curriculum. “I wanted students to think way beyond the classroom,” Pollock says. “I wanted them to feel empowered. I wanted them to realize how bright they were.” The key, he decided, was helping them achieve professional — not undergraduate — levels of success. He designed a research-intensive method that mimicked the stages of article production. Coining it the “Communication Commando Model,” he warned students it might feel a bit much at first.

Instead of tackling an array of unrelated essays and exams, Pollock’s students immersed themselves in one semester-long project. The paper that emerged from their work wasn’t meant to earn a passing grade to maintain their GPA, but to make a serious contribution to the field of communication studies. There were extensive literature reviews and deep dives into methodology. And, in what became a brace-yourself rite of passage for thousands of students, there were Pollock’s regular and very public in-class edits of works in progress.

“It was terrifying,” says Kelsey Zinck Chado ’14. “It wasn’t you just getting back red marks to yourself, where you could sit and sulk at your desk. It was a reality check in a public forum.”

But she found that she loved both the process and the demanding but charismatic professor who wore suits with a cowboy hat and told vivid stories about books he’d written, fieldwork in South America, and his teenage years riding horses in Colorado. Though she’d planned on a career in sports communications, publishing and presenting her paper from Pollock’s class about health conditions in Guantanamo Bay inspired her to instead pursue a master’s degree in public health.

“It was a total turning point,” says Zinck Chado, program manager at the Cystic Fibrosis Foundation. “I felt like I wasn’t just a college kid going to class. It was the first time I felt like I could really see a career path.”

She wasn’t alone. Pollock’s high expectations and attention helped set scores of students on postgraduate paths they hadn’t imagined possible. When Ichiro Kawasaki ’08 began Pollock’s introductory public relations course, he was a junior in a quiet panic about a future he couldn’t quite picture. But the work he did in class sparked an interest Kawasaki hadn’t felt in other subjects.

Pollock encouraged him to consider a communications career, connecting him to an internship at a local PR firm and later helping him apply to graduate schools. That step-by-step support launched a career that rocketed Kawasaki to the top of a Big Four accounting firm. “When I think about people who have impacted me the most in terms of my professional life, it would really start with him,” says Kawasaki, now senior director for public relations at KPMG. “He saw something in me that no one else did. And if he hadn’t seen it, I don’t know where I’d be today.”

As much as Pollock’s name remains top of mind for alumni like Kawasaki, their stories and successes have also helped Pollock inspire new generations of students. Soon after Lauren Longo ’15 arrived in Pollock’s class her sophomore year, she began to hear about “The GreatTom Hipper” and his legendary presentation at the Kentucky Health Communication Conference. “Dr. Pollock loves to talk about the students who came before you,” says Longo, associate director of advocacy and communication at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. “And then the next generation comes, and they hear about you. He always wanted to push his students — it sounds cliché to say — to reach their top potential. But it’s absolutely true of him.”

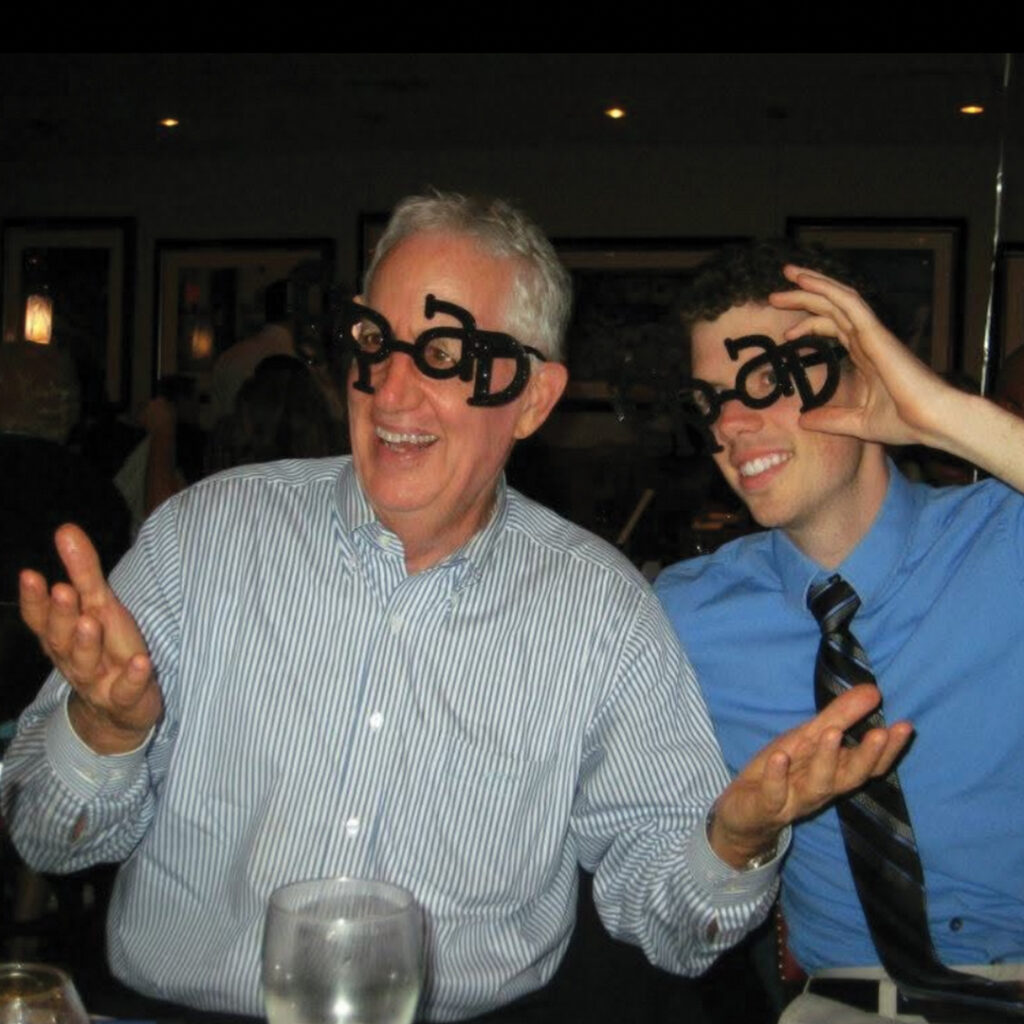

Two years ago, Longo was one of a dozen former students who attended what she thought was Pollock’s 80th birthday party but turned out to be his surprise wedding to writer Margaret “Peggy” Mandell. “I never wanted to retire ‘from,’ just for the sake of retiring: I wanted to retire ‘to’ something,” he says. “Now, life with Peggy is absolutely glorious. Now, I have something to retire ‘to.’”

In the meantime, Pollock is ready for his last semesters. As always, his door will be open. Some students might discover a mentor who sends them down a new path. Others may find inspiration and role models in his stories about the graduate school acceptances, published papers, and conference triumphs of the scholars who’ve preceded them. Pollock’s message to the students just starting out is simple but powerful: “They were students just like you, in this very same class,” he says. “These aren’t magical people with magical powers. And look what they’ve been able to do.”